WHY ISDA AGREEMENTS ARE ONE-SIDED, AND HOW IT COULD AFFECT YOUR COMPANY.

It should come as no surprise that the International Swap Dealer Agreements (ISDA) today’s multinational corporations sign with banks tend to be one-sided. If the bank defaults on a corporate customer (think Lehman Brothers), there’s no opportunity to collect on collateral. All of this may work well for the banks, but not so well for your company. This paper looks at some of the problems associated with over-the-counter trading, and specifically how it relates to counterparty risk mitigation.

ISDA Review

A critical component to any over-the-counter (OTC) trading relationship is your ISDA agreement, specifically the schedule to your master agreement and your Credit Support Annex (CSA). As many corporate financial professionals know, an ISDA agreement is the cornerstone of any transactional relationship between two parties engaged in OTC financial transactions. An ISDA agreement is composed of three major components:

- Master Agreement – Standard language shared among all parties to execute ISDA agreements.

- Schedule to the Master Agreement – The terms that have been negotiated between the two parties thatspecifically contrast what’s been outlined in the Master Agreement; or language that potentiallyenhances understanding of, or further modifies, the Master Agreement.

- The Credit Support Annex (CSA) – This is the third and separately negotiated piece of documentation that outlines what would happen to address credit risk that the counterparties have to each other. For example, it may be a common practice in your CSA to have the posting of collateral to the extent that either of the parties is downgraded by a nationally recognized rating agency; or, if there’s some type of default event, technical fault or actual default, that could result in additional collateral posted by either counterparty.

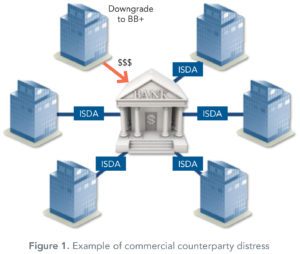

Figure 1 illustrates how a Credit Support Annex might work. The company in the upper left has just been downgraded to a “BB+” rating from “investment grade,” and the banking counterparty notifies them that a) they’ve violated the terms of their CSA and b) they need to post additional collateral, because the trade – or the net of all their trades they have outstanding with this counterparty – is out of the money.

The key thing to notice in Figure 1 is that the bank has ISDA agreements with all the participants, whereas individual companies typically only have an ISDA agreement with the bank, or potentially multiple banking counterparties. Individual companies don’t have nearly as many ISDA agreements as the banking counterparty has with other commercial clients.

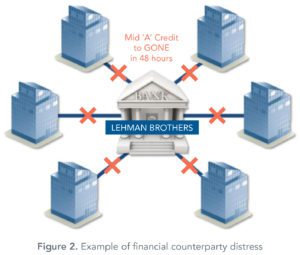

Figure 2 illustrates what we’ve seen happen over the last couple of years. Our banking counterparty example in the middle is Lehman Brothers, which moved from a “Mid A” credit rating to basically going bankrupt over the weekend. There was no opportunity for the commercial counterparties to demand collateral from them, and they probably wouldn’t have received it. In fact, when Lehman went under, they had over 8,000 master ISDA agreements signed and over 67,000 open trades.

This is the state of ISDA agreements as they exist today. A typical CSA may call for the exchange of collateral at a level of “BBB” or lower. This results in a one-sidedbenefit for the bank, with no practical benefit for the commercial counterparty. A commercial counterparty may be able to operate just fine with a BBB rating, or even in an environment below “investment-grade” for quite some time, giving the bank ample opportunity to receive collateral under a typical existing CSA.

Conversely, a change in a major bank’s credit rating to the same level would be a proverbial nail in their coffin. Sufficient capital would have already left the bank, and the bank’s cost of funds would have already increased to a level that would make operating as a bank impossible. So as they exist today, CSA’s only provide a false sense of security to the commercial counterparty.

What your company can do to help protect itself?

Companies have largely taken two different approaches to correct for what they see as one-sided CSAs that favor the financial counterparty: using third-party collateral managers, and trading on a listed futures exchange.

Many companies arrange for third-party collateral managers to accept and remit collateral – based on the market-to-market status of the outstanding trades – to each financial counterparty. While the daily posting of collateral tends to be the most effective way to ensure the credit worthiness of your OTC counterparty, it tends to be very cumbersome for both the commercial and the banking counterparty.

“Re-hypothecation”

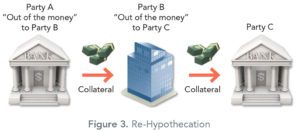

Beyond the operational complications of posting collateral on a daily basis, arrangements with the third-party collateral manager can become further complicated due to a practice known as “re-hypothecation” illustrated in Figure 3.

In this example, Party A is out of the money on a trade, or a series of trades, to Party B, and is therefore required at the end of the day to post the collateral. In this example, Party B is the commercial counterparty, which actually has no net position in this particular transaction due to the fact that it has an equal and offsetting trade to counterparty C. So while Party A is out of the money to Party B, Party B is also out of the money to Party C. Party B therefore passes on the collateral that it received from Party A to Party C, i.e. Party B has “re-hypothecated” Party A’s collateral.

Where this situation gets even more interesting is when Party C goes bankrupt, and Party B is left to deliver a termination notice to Party C. Party B is essentially forced to re-issue the equal and offsetting trade that it had to counterparty A.

Most re-hypothecation risk is due to operational issues. It could take a long time for you to discover that Party C has gone out of business, deliver your termination notice, and then to go ahead and put on new trades with another counterparty to replace the trades that you just terminated. During this time, you’re completely exposed, as the value of those trades could be moving rapidly in what is likely a very volatile market. This explains why there’s currently a lot of dialogue in the Financial Reform Bill over the subject of central clearing for over-the-counter transactions.

While nothing has been firmly decided, it certainly appears that market participants will be encouraged to clear their transaction centrally. Atlas poses this question to the commercial counterparty: Why would you wait? It’s a far more effective solution. In the scenario above, there wouldn’t be any remaining credit exposure for the commercial entity, which would have offsetting trades with the clearing firm. You would no longer have a position in that currency or interest rate at all, as opposed to having two equal and opposite transactions with two different counterparties.

A BETTER RISK MITIGATION STRATEGY: TRADING ON A LISTED FUTURES EXCHANGE.

The good news is that there is a solution available today: trading your currency and potentially some of your interest rate volumes on the CME (Chicago Mercantile Exchange) using a generic futures contract. The futures market is incredibly deep, with over $100b in daily liquidity, and handles all the collateral arrangements for you. In addition to more efficient handling of the collateral, trading on a listed futures exchange offers much more transparent pricing: you have the ability to join the bid or join the offer depending on which side of the transaction you wish to participate.

There are plenty financial institutions complaining in the press right now about the possibility of moving the central clearing, and moving to exchange listed contracts. They don’t mention the CME in particular, but these shifts would have a huge negative impact on profits in the banking sector. Atlas has found that commercial counterparties generally lack the knowledge, and therefore the motivation, to prevent the financial counterparties from taking advantage of them in these over-the-counter transactions.

THE PROS AND CONS TO TRADING ON A FUTURES EXCHANGE.

Figure 4 illustrates the advantages and disadvantages of trading on a listed exchange for your currency or interest rate volumes. Again, futures markets are sufficiently deep. You only have a single name as counterparty with an established record for addressing collateral arrangements. You also have anonymity in dealing, which equates to better pricing.

Advantages

- Futures markets are sufficiently ‘deep’ to address trading volume for most corporates – block trading OTC can address liquidity issues for larger trades and/or less liquid contracts

- Only a single name as counterparty with established record for addressing collateral / credit risk

- No credit value adjustment (CVA) in pricing

- Anonymity is dealing = BETTER PRICING

DISADVANTAGES

- Cash (or T-Bills) must be posted as initial collateral and must be maintained based on mark to market of contracts. (This used to be more difficult with most cash offshore but now is more realistic option for clients with onshore cash)

- Liquidity for new monthly contracts is not as deep as old Dec, Mar, Jun, and Sept contracts. Block trading can address this

- Swaps not readily available and must be traded OTC and far legs booked via block trade.

Figure 4. Pros and cons of trading on a futures exchange

The main disadvantage to using futures contracts used to be that they only mature four times a year and must be traded in notional amounts that are compliant to the exchange. As of March 2020, all contracts now have monthly maturities (except CHF and NZD) and therefore would suffice for income statement hedging activity (ASC 815), which requires cash flows to occur in the same month as the hedge.

At lot of risk management professionals—particularly currency risk management professionals—are thinking about cash flow transactions and how problematic those would be with hedging using futures contract. But Atlas feels that to the extent you’re doing balance sheet hedging correctly, one shouldn’t be conducting any spot transactions in the middle of the month, anyway.

So, to the extent you’re in need of a cash transaction, you’d really facilitate that using a swap, where you’d be buying and selling a particular currency. Using futures contracts, there is a way to book what they call a block transaction, where one can essentially call up an over-the-counter counterparty and book a swap where you maintain the near leg as a cash transaction—which, due to its near-term maturity, carries little credit risk. The far leg would be booked to a futures-compliant date in a futures-compliant amount. You would then simply call up the CME and convert that over-the-counter contract into a number of futures contracts, and now it would be booked to the futures exchange.

In the current environment, Atlas Risk Advisory feels it’s just a matter of time before central clearing and exchange listed transactions become a reality. We can help you navigate the transition to central clearing and futures contract trading while adding value in your risk management activities and other areas as well.

If you’re a multinational company seeking an external FX risk management firm with deep expertise, the latest software solutions, and a proven execution component, please contact us for a free consultation today.

Disclaimer

The information contained in this publication is provided for information purposes only. The information contained herein has been obtained or derived from public sources believed to be reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete and should not be relied upon as such. Any opinions or predictions constitute our judgment as of the date of this publication and are subject to change without notice.

All rights reserved. Please cite source when quoting.